This is a commentary and comments are welcome by email to info@eaa.co.ke

EL NIÑO AND LA NIÑA IN EASTERN AFRICA

What is El Niño and La El Niña

El Niño a Spanish phrase that translates to “Little Boy” is a phenomenon caused by above-average temperatures on the surface of the sea in the tropical Pacific Ocean. This in turn causes warming in the earth’s atmosphere with rising moisture causing rainstorms. On the other hand, La Niño, translated to “Little Girl”, is the increasing cooling of waters in the Pacific that result in dry spells. According to NASA, the two appear in cycles of 3-7 years with El Niño following La Niña. While they occur in the Pacific, they have the effect of changing weather patterns globally.

As Eastern Africa relies heavily on agriculture, the impact of El Niño and La Niña have had devastating impacts on the countries in the region ranging from prolonged periods of drought followed by periods of unusually heavy rainfall. Changes in rainfall patterns in countries that are reliant on agriculture do affect the “health and economic prosperity” according to SpringNature.com, a fact which we are well aware of and are experiencing currently.

Agriculture and the region

|

“The agricultural sector is dominated by smallholder mixed farming of livestock, food crops, cash crops, fishing and aquaculture. The major food crops are maize, rice, potatoes, bananas, cassava, beans, vegetables, sugar, wheat, sorghum, millet and pulses”. East African Community |

The East African Community (EAC) estimates that 70% of industries in the block are linked to agriculture. Intra-regional trade volumes in the block arise almost two-thirds from the sector.

The World Bank indicates that almost 400 million of the poorest people in the world live in Sub-Saharan Africa, with the majority of them living in rural areas and reluing on agriculture for their daily existence. The impact of both El Niño and La Niña on the drive to reduce poverty is creating an uphill battle for Governments in Eastern Africa.

However, these two phenomena, devastating as they can be, are not the only factors that are affecting the agricultural sector in Eastern Africa. The impact of Climate Change is also having a far-reaching impact on agriculture despite Africa only contributing 3.6% of global emissions. If global temperatures rise by between 1.50 C and 20 C, the World Bank believes that between 40% – 80% of cultivation areas will be affected. A sobering thought indeed. The United Nations has said that Africa annually loses 12 million hectares of land that could be used for agriculture with the associated impact on food security, poverty reduction, and the distinct possibility of conflict between countries.

A crisis that is unlikely to get better

Credendo, a European credit insurance group, in an article on their website – “East Africa: A Climate Crisis that is Only Expected to Worsen” – points out that the region has faced severe drought conditions in the last six rainfall cycles. This was caused by La Niña probably “exacerbated by global climate change given that small changes in sea-surface temperatures can lead to bigger changes in weather patterns”.

Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya were the hardest hit by this, and famine conditions continued from 2020 to 2023. Matters were not helped by the locust invasion – the worst in 25 years in Somalia and Ethiopia and 70 years in Kenya says Credendo. 23 million people are estimated to have faced “severe hunger” and 10% of them relocated in search of food for both themselves and their livestock creating a significant refugee crisis. Armed conflicts in these countries further added to the woes of the population.

The lack of rainfall also impacted electricity generation from hydropower plants in Kenya and Tanzania. Fortunately, both countries, whether by luck or by design, have been reducing their reliance on this form of power over the years substituting it with other sources – gas in Tanzania and wind and geothermal in Kenya.

Of course, La Niña was followed by El Niño which started in mid-2023 but unleashed its fury in April 2024. One would have thought that this was good news, but the drought conditions that existed meant that “arid soil could not absorb the water” resulting in floods and landslides. The effect once again, is the movement of people to find less dangerous areas to live in.

However, it doesn’t end there! Floods bring with them a high risk of diseases such as typhoid and cholera and of course, create a superb breeding ground for mosquitos and thus malaria. In addition, infrastructure that was never built to deal with the level of rainfall witnessed is crumbling around us.

In a region where Government resources are already stretched to the limit and debt distress is increasing, El Niño and La Niña are the last things we need. With Climate Change a daily occurrence today, it does seem that El Niño and La Niña will move close to the lower end of the 3 – 7 year cycle, which is far from welcome in Eastern Africa.

Lack of preparedness

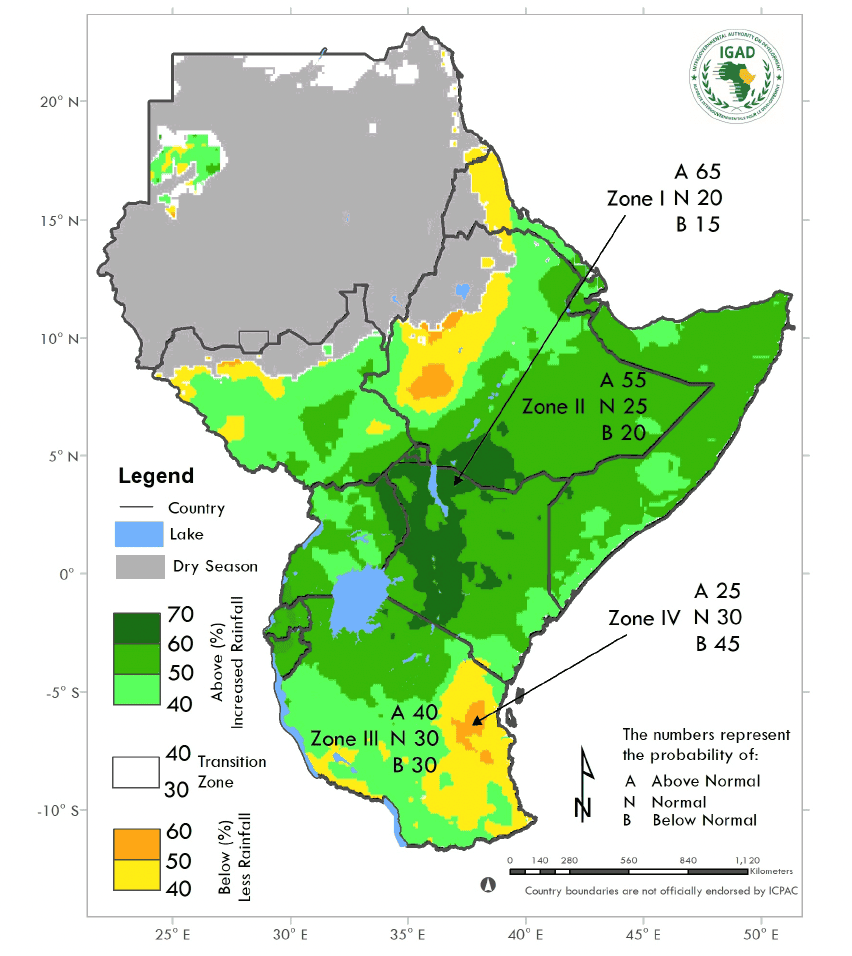

the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC) said in early March this year that the region should expect greater than usual rainfall this year. Indeed, other organisations were predicting this during much of 2023 but the Regional Government, in their eternal wisdom, ignored the warnings. The Met Office in the United Kingdom was of the same view with one of their officials saying: “It can bring record-breaking rainfall in seasons forecast to have even drier than normal conditions”. And so it came to pass.

Coupled with this, the official said that 2023 witnessed record-breaking temperatures and these are likely to persist, and indeed surpass, in 2024 partly because of Climate Change and the fact that El Niño “releases a significant amount of heat into the atmosphere”.

As said above, the coming of El Niño was predicted at least a year before it hit the region with incredible force. Yet no precautionary measure seem to have been taken. Virtually all the countries in the region are experiencing flooding, landslides, and crumbling infrastructure. With the heavy rainfall, the inadequacies of the region’s drainage systems have come to the fore. Years of unplanned development have put pressure on the infrastructure and are having a massive effect on the population.

The United Nations has reported that El Niño has affected Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. An estimated 5.2 million people were affected by floods in the last quarter of 2023 and more are currently being similarly affected.

How long will it last?

Reliefweb predicts that the current El Niño will last until June 2024 and this has also been echoed by Kenya’s Meteorological Department.

In the last half of 2023, Reliefweb says “El Niño triggered droughts, wildfires, heatwaves, heavy rains, and floods in many parts of the world. These include severe droughts in Central and Northern South America and Southeast Asia and the Pacific, as well as flooding in East Africa”. Global temperatures are reported to have increased by 1.480 C which is “dangerously close” to the threshold of 1.50 C. Ocean surface temperatures are also at record levels, partly because of El Niño but also due to Climate Change impact.

The first six months of 2024 will see much the same and the humanitarian crisis in many parts of the world is becoming a serious issue. Global temperatures are expected to be higher than average which is a concern and may well cross the 1.50 C threshold. Reliefweb believes El Niño has reached its peak “but its consequences will be felt for the remainder of the year”. East and Southern Africa are likely to see an acceleration in vector-borne diseases such as zika, dengue, chikungunya, and malaria, and outbreaks of cholera and typhoid are distinctly possible.

The future

While predicting the future is nigh on impossible, we perhaps know with some certainty that adverse weather events are more than likely to occur. For the Eastern Africa region funding the preventive measure is likely to be the key obstacle. Grace Ronoh, a Kenyan climate activist, said at the annual IMF and World Bank meeting: “When you look at especially the developing countries, they are not able to prioritise a response to the climate crisis because for them to do this, they require financing. And at this point in time, most of the countries are debt-laden, so they will prioritise paying for debt”.

While funding is critical, Eastern African Governments must show willingness to be prepared which in the current spell of rainfall it is apparent we were not.

|

“Policymakers need to plan for this. In the long term it is crucial to ensure that any new infrastructure is robust to withstand more frequent and heavier rains, and that government, development and humanitarian actors have the capacity to respond to the challenges. Better use of technology, such as innovations in disseminating satellite rainfall monitoring via mobile phones, can communicate immediate risk. New frontiers in AI-based weather prediction could improve the ability to anticipate localised rainstorms, including initiatives focusing on Eastern Africa specifically”. The East African |

This is a commentary and comments are welcome by email to info@eaa.co.ke