EAA analysis on trends in the global and regional economy, in the wake of a the pandemic, supply chain interruptions and the war in Ukraine.

ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: Prospects for the global and regional economy

Global economy

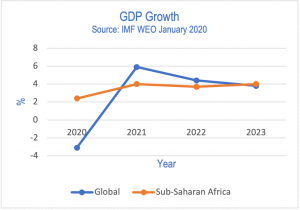

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) released its latest update on the world economy in January 2022 saying that the world was in a “weaker position” when compared to its previous update in October 2021. This prediction was before the current war in Europe between Russia and Ukraine which is expected to make matters worse. The IMF has reduced its forecast for global GDP growth from 5.9% in 2021 to 4.4% in 2022 (0.5% lower than the forecast in their October 2021 update) and slowing further to 3.8% in 2023. Their latest outlook, released this month, takes account of the conflict and the forecasts for 2022 and 20223 have been lowered to 3.6% for both years.

Factors that have contributed to the drop include the rising surge in Covid infections caused by the Omicron variant with some countries introducing restrictions. Interestingly, most countries which have seen a surge did not lock down believing that mankind would simply have to live with the virus. Importantly, none of these countries seem to claim that Covid-19 is moving from pandemic to endemic. Despite the surge in Omicron, many countries have eased restrictions on the grounds that it was not creating significant illness. However, the new B2 variant seems to be headed in the opposite direction. In the last month, China has locked down 50 million people in keeping with its zero Covid stance.

Global growth has also been affected by increased oil prices and continued supply chain disruptions, certainly not helped by the China lockdowns and indeed the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This is expected to impact inflation which is now steadily rising across the world. China’s real estate sector continues to slow and global consumption has not picked up. The two largest economies in the world, the US and China, are expected to see a drop in GDP growth of 1.2% and 0.8% respectively, which the April outlook reduces further for the US by 0.6% in 2022 and 0.2% in 2023 and in China by 0.4% and 0.1% respectively. Sub-Saharan Africa, which in recent years has bucked global trends, has fallen back but is projected to catch up in 2023.

The pandemic

Daily deaths decreased 30% since October when compared to August 2021. This is largely attributed to the vaccine roll-out where it is estimated that 55% of the world’s population has received at least one dose. Unfortunately, this does not apply to Africa which continues to lag behind the rest of the world but nonetheless is seeing a marked reduction in daily infections. The current forecast assumes that vaccination roll-out will be at 60% for the first dose by June 2022. It also assumes that countries will continue with track, trace and test protocols even though the reality is that most countries are no longer doing this. Should the world experience different and more severe variants in 2022 and into 2023, the picture may be significantly bleaker.

Supply chain disruptions

Supply chain disruptions are by no means new – the world has experienced these in the past and will no doubt continue to do so in the future. Disruptions take many forms and affect many sectors of the economy, either as a whole or in parts with varying degrees of intensity, some easier to deal with than others.

Natural disasters often cause disruptions as factories producing critical inputs for other parts of the world shut down – for example, in 2011 in the US, a specialist paint manufacturer for cars was shut down because of an earthquake and tsunami warnings resulting in a backlog in car production. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 disrupted the progress of container ships through the Gulf of Mexico. 2015 saw the shooting down of a Russian plane by Turkey with the resultant blockade of cargo from Turkey to Russia.

There are of course other factors that create disruptions and Covid-19 has clearly been one that has had significant impact which may well continue through 2022 and 2023. The current Russia-Ukraine crisis with sanctions and closure of shipping lines is also creating immense downward pressure on global economies.

Most of the transportation of goods is by sea and backlogs at the major ports around the world have meant that containers are just not where they should be. Some freight lines have taken to offloading cargo at a port and rather than waiting for outbound goods, have simply sailed empty to another port. As the pandemic raged, the issue became worse with a lack of loaders at the ports. The net effect has been an increase in freight costs resulting in higher consumer prices globally. This has perhaps depressed consumer spending which in turn has given rise to a drop in economic growth. In a sense we find ourselves in a vicious cycle with no light at the end of the tunnel.

But what do suppliers do in these circumstances?

The world had virtually perfected shipping pre-pandemic with suppliers using the “just in time” concept ensuring goods were where they should be to meet demand at the right time. That may well be not so easy anymore and inventory levels may have to increase, with associated cost rise, to ensure that goods are available when needed, particularly as online shopping becomes the norm.

We may also see a shift away from globalisation to local manufacture and production. This may not be a bad outcome for emerging economies such as those in Eastern Africa, but on the other hand, this will need significant expenditure on infrastructure by these countries. With China being the leading manufacturer to the world and its zero Covid policy, continued mass lockdowns in the country may well mean that local production becomes a must. The bottom line seems to be that companies are necessarily going to have to rethink their supply chains and relatively quickly.

Suppliers will need to consider other options for their sourcing and that too may not be easy. Some inputs – microchips for example – require specialist production that is not available everywhere. Indeed the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan clearly demonstrated this. Of course, this does present opportunities that can be considered, provided the investment funding is available. The connection between buyer and seller is going to have to improve with clear and transparent visibility of each other’s requirements and practices. Greater collaboration should really become the order of the day.

At times of geopolitical instability – the Russia-Ukraine crisis and indeed even the forthcoming elections closer to home, in Kenya – needs to be carefully monitored. Planning for this may not always be simple but it is not impossible. Where business is aware that a major geopolitical event is happening – like elections for instance – advance planning could ease the disruption.

At the end, what is really required is a robust and resilient supply chain, that can deal with most, if not all, eventualities.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict

In the last week of February 2022, war broke out in Europe between Russia and Ukraine and the economic impact of this conflict is likely to be significant, both for the two countries involved, and the world. Russia, according to the IMF, was the world’s eleventh largest economy, and a major exporter of oil and gas not to mention basic food commodities. Ukraine, too, is a major exporter of food with considerable amounts coming to Africa.

The West rapidly imposed crippling sanctions on Russia including seizing assets of the Russian Central Bank and citizens abroad, restrictions on access to the global Swift system and halting the commissioning of Nord Stream 2, the new Russia-Germany gas pipeline. These sanctions will no doubt hurt Russia’s economy, though tempered somewhat by rising commodity prices to the extent the country can supply them given the sanctions. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research is projecting a drop of 1.5% in Russia’s GDP in 2022, which in the circumstances may be optimistic. There may be an unintended consequence to the sanctions, in that inflation is spiralling globally, and basic food commodities are becoming scarce in the developing world. India and China appear to be ignoring the sanctions and in addition, Europe continues to buy gas from Russia, although the Russian Government is attempting to force purchases to be completed in Roubles. The IMF expects Russia’s economy to contract significantly as a result of the conflict and resultant sanctions.

The IMF sees the impact of the conflict arising from three channels: “(1) Higher prices for commodities like food and energy will fuel inflation, in turn eroding the value of incomes and weighing on demand. (2) Neighbouring economies, in particular, will grapple with disrupted trade, supply chains and remittances as well as a historic surge in refugee flows. (3) Reduced businesses confidence and higher investor uncertainty will weigh on asset prices, in turn tightening financial conditions and potentially spurring capital outflows from emerging markets”. Given the conflict, the IMF has indicated that it will reduce its growth forecast but still anticipates there to be growth globally.

Sub-Saharan Africa imports 85% of its wheat requirements and one third of this comes from either Russia or Ukraine. As the conflict continues and supply is disrupted, expect to see inflation spiralling as the commodity price increases. This will be devastating for the region which was gradually coming out of economic turmoil following the pandemic. Fiscal deficits are likely to increase and pressure on Government finances will be difficult to deal with. The balance between inflation and support for recovery of post-pandemic economies is likely to be a difficult one.

Sri Lanka defaults

Just prior to the Easter holidays, the Sri Lankan Government announced that it would suspend payment of its foreign debt. The country has been facing large scale protests on the streets against the Government’s handling of the economy, high inflation and rising interest rates. Much of Sri Lanka’s debt is external, requiring USD 7 billion to service this year against foreign exchange reserves of USD 1.6 billion hence the country is now seeking assistance from the IMF.

A few years ago, the country’s economy seemed to be doing well with tourism and exports. Covid-19 and now the conflict in Europe has seen a significant decline in economic activity not helped by some ill-advised tax cuts by the Government. A lack of fuel and erratic power supply has put paid to the manufacturing industry, and protests and curfews coupled with shortages of most commodities have meant that the tourism sector is at a virtual standstill.

Sri Lanka is not the only country in the world to experience an economic downturn in 2022 and it is quite possible that other countries could also default in the near term.

Closer to home

The Eastern Africa region has, by all accounts, started to emerge from the economic hardships of the pandemic. There certainly seems to be more positivity in the economies but there also remain several hurdles.

Firstly, while Covid infections have dropped significantly since late October 2021 when compared to August 2021, the Omicron peaks in late December and much of January, still saw most countries lift restrictions, and the danger of another wave remains. The fragile economies will likely struggle with this which therefore continues to be a concern. All the countries have a significant reliance on tourism and continued waves of the virus could have a massive impact.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict and its impact on oil and commodity prices is resulting in higher inflation as prices soar. In countries where poverty is prevalent, this certainly is not good news.

Thirdly, the regions’ largest economy, Kenya, will hold general elections this year and all eyes will be on this. While there is no reason to suppose that the elections will be disruptive, a repeat of what happened in the past, might impact the country and its neighbours.

The conflict in Ethiopia continues, albeit with a lesser intensity than in the recent past, and this will continue to impact that economy and perhaps some of its neighbours.

But there seems to be positive news and opportunities as well.

With supply chain disruptions continuing, opportunities may present themselves for local investments in manufacturing which will certainly help. Inbound investment is still available and interest in the region remains high.

Tanzania and Uganda, with significant oil & gas resources, may well benefit from the conflict in Europe. As sanctions continue against Russia, the two countries are likely to see greater investment in this sector.

Meanwhile, the East African Community recently admitted the DRC as a Member State which brings with it another 90 million people into the market. The nuts and bolts of the admission are still being worked on, but the upside is positive.

Where are we headed

The world was witnessing a post-pandemic recovery which the Russia-Ukraine conflict has undoubtedly slowed down. It is difficult to say how long the conflict will last and indeed what its long-term impact on the global economy will be. Suffice to say, in the short-term the world will see a slowdown in growth.